For a congress on sustainable collective housing, being a concept that has been formed through adjectival aggregation and us being a team that works from a project-based standpoint, we propose our contribution be describing specific cases: projects that have led us to consider what today’s spaces for collective life could be like.

First of all, we will look at three projects that took place more or less simultaneously, which each tackled a view of housing in terms of collectivity and sustainability. The goal is to start by translating the terms that will allow us to tackle this topic into our own vocabulary, which is that which comes from formulating and developing declarations, which are desires in search of a way to become reality. This text is that part.

Secondly, three examples of sustainable collective housing projects developed through activism, teaching and professional commission, respectively.

Housing + Collective + Sustainable

SUSTAINABLE or Trying to be eco-friendly

The term Sustainability, widespread today, is too abstract. Everyone, or almost everyone, agrees that we have to be sustainable. But there’s no sense that humanity has organised to achieve this goal. This is surely due to the term’s newness. It wasn’t until 1987 when Norwegian Prime Minister Gro Harlem Brundtland used it at the United Nations in the report Our Common Future, defining it as follows: “Humanity has the ability to make development sustainable to ensure that it meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” Meaning, let’s leave behind a world that is better, or at least as good, as the one we were born into.

The implicit message is a clear view of the finite nature of the planet’s resources, a criticism of how humanity has overexploited the environment with no respect, and a call for an attitude shift with apocalyptic overtones. Being sustainable as an ethical duty on a global scale.

But 40 years later, we have done next to nothing. It seems like the issue is in the hands of governments and large transnational organisations with agendas and goals to achieve by 2020, 2030, 2050. But, as citizens, what can we do to be more sustainable?

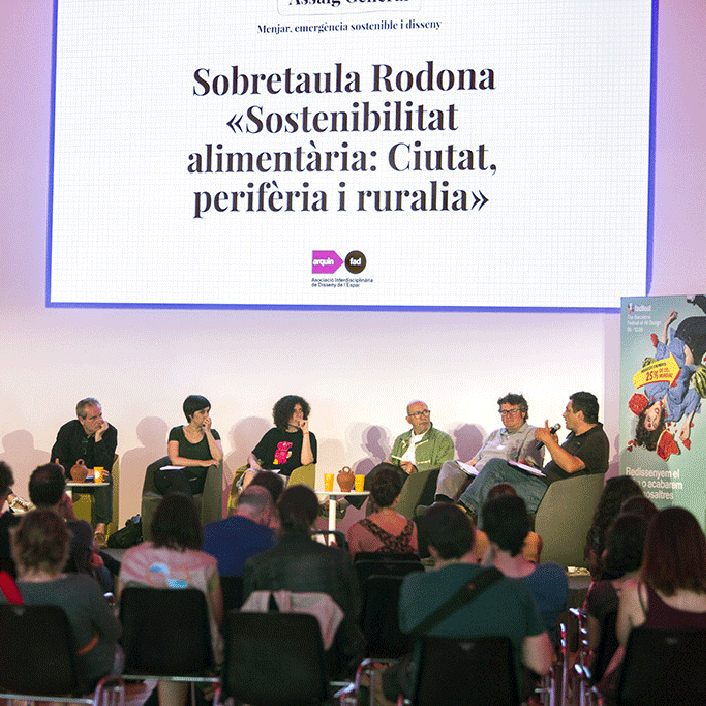

Dress Rehearsal, FAD, 2015

We were faced with that question when we were asked to curate and design an exhibition on sustainable design. Specifically, the goal was to share examples of how the various branches of design (space, graphic, product, communication, etc.) were using design to address the non-negotiable need to be sustainable.

Our first answer was to change the declaration for a different one. Questioning the “what” and the “how”. What would happen if, for just one day, all of our actions were completely sustainable? What and How should we design to achieve this?

This declaration gave rise to a specific challenge: hosting a popular meal that was delicious and sustainable. Specifically, feeding 900 people good food in a comfortable environment, at a great culinary celebration in which each and every one of the decisions necessary to carry it out chose the more sustainable option.

We questioned everything: How is food produced? Where does it come from? How is it transported? Why are ugly foods thrown out? Why is everything in packaging? How is it cooked? How is it consumed? Why do we waste so much? Where does our waste end up? What waste is generated? What happens to it?

Dress Rehearsal became a rehearsal of sustainability on an urban scale, which meant forging alliances in the area with loads of people. Scientists, activists, neighbours, chefs, transport professionals, bakers, journalists… and designers all participated in this event, which acquired the structure of a huge co-production.

COLLECTIVE or the world of Co&Co

Collective life has existed since the dawn of humanity. In fact, communicate, share and co-exist are verbs that define humanity.

In recent years, in Barcelona, Catalonia, Spain, we’ve seen a resurgence of collective consciousness. Many people have mobilised again and a new sense of renewed, emancipated activism has appeared, uniting people not only under a shared cause but also around the desire to propose alternatives and, therefore, work on projects collectively.

Cooperative Architecture, Barcelona, 2015

Conferences on citizen participation at the COAC

Faced with the growing desire of some citizens to take part in the processes transforming the city, we proposed that the Catalan Association of Architects host a series of professional conferences focusing on the active role of architects in participatory processes and the tools needed to make real participation possible, suitable and useful.

The seminars are aimed at both architects, who as citizens are part of specific participatory processes, and those who, given their professional role in government, need to integrate participation processes into their work serving residents. The goals were to: share tools and methodologies for citizen participation; define appropriate conditions for carrying out citizen participation processes; promote a useful role for architects in citizen participation projects and processes; and share knowledge and coordinate initiatives.

The seminars were conceived based on three starting points. Firstly, recognising and contextualising an emerging social reality: people’s growing demand and desire to be part of the processes transforming cities. The normal forms of urban and architectural design are based on a framework of interests that excludes most of the stakeholders involved and/or affected by the transformation, mainly residents and those who use the spaces. The goal of participatory processes is to include these agents in the process of urban planning and architectural design for the space.

Secondly, recognising the value and poetry of collective intelligence in developing a project. To seek out mechanisms that make co-creation possible. Participative design consists in finding inclusive ways to integrate stakeholders involved in an urban development or architectural project. These projects are structured in a way that is adaptive and organic. A collaborative, creative, open process that puts decision-making power in the hands of local experts and stakeholders. But we have to learn to play in the CO worlds.

Finally, recognising the shortcomings of the current conditions and proposing changes, both in the world of teaching and in public administrations.

The first and main success of the conference was that it was held at all. This was the first contact the Catalan Association of Architects had with cooperative architecture and participation, reaching people who had not actively participated in the institution’s activities previously.

HOUSING or A place to live

This term implicitly implies protection, a place where basic needs are met and guaranteed. Therefore, in our culture, a separation between domestic life and day-to-day life. Shelter versus the outdoors.

Zero Flat, Barcelona 2015

Zero Flat is an experimental housing project.

Arrels Foundation, an organisation based in Barcelona that provides help to those living on the street, found it frustratingly difficult to help some users, who rejected the shelter they were offering.

There were many different reasons. Some, psychological, involved the fear of “having again and losing again”. Others came from a rejection of vacating the fixed spot they had won on the street. But there was also a reason where we could try to be useful doing what we, as architects, know how to do. The fact is that, for some of them, going to a flat, a hostel or a residence means following basic rules of co-existence that are impossible for them. Having to abandon their animals or carts on the street, not being able to smoke, not being able to leave, having to take a shower. There weren’t housing options that fit their case and they rejected the help, making their situation chronic.

Arrels proposed we experiment with a different type of accommodations, while adapting their own protocols with volunteers. They called it “low-demand accommodations” and posited an attitude change: not giving them the solution, but looking for one in each user and adapting to them. Design after listening.

This situation allowed us to consider housing in a new way, based on the essentials, without taking anything for granted, starting off by listening to those who didn’t have a home and lived on the street. The homeless build their own sort of protection, shelter and social/domestic life outdoors.

Sustainable Collective Housing

After reviewing these three concepts, Sustainable + Collective + Housing, we understand that what we’re talking about is “living together in the same world”. Let’s talk, then, of Architecture of Domestic Co-existence, between people and the environment.

We’ve always lived together, in caves, homes, settlements, neighbourhoods and cities, without having or needing any sort of project. Only specific communities, like religious ones, lived collectively under an architectural model of co-existence. Until industrialisation and the need to house many people with few resources and less time.

With this, we’ve experienced the debate on how semi-public spaces are handled, the wide variety of types, how they adapt over time, the character that, given its architectural dimension, housing confers on the city. But collecting housing, as an architectural project of life as a collective, consists in designing conditions to co-exist.